FRED SAUCEMAN is author of the forthcoming book Buttermilk and Bible Burgers: Stories

from the Kitchens of Appalachia.

We don’t think much nowadays about how turkeys get from farm to market to oven. But

from around 1884 to 1920, in rural, mountainous Hancock County, Tennessee, it was quite an

undertaking. Imagine moving hundreds of turkeys 35 miles over rugged land and rough water.

Imagine keeping track of which turkeys are yours and which belong to your neighbor. Imagine

what happens at evening roosting time when the turkeys take control and head for the trees.

Imagine your disappointment when, at the end of that long turkey trek, you don’t get the price

you’d hoped the birds would bring.

Scott Collins of Sneedville, Tennessee, isn’t old enough to remember the legendary

turkey drives of his home county, but he has studied the strange practice as much as anyone.

Scott can talk turkey. After a 32-year career as a court administrator, he now negotiates

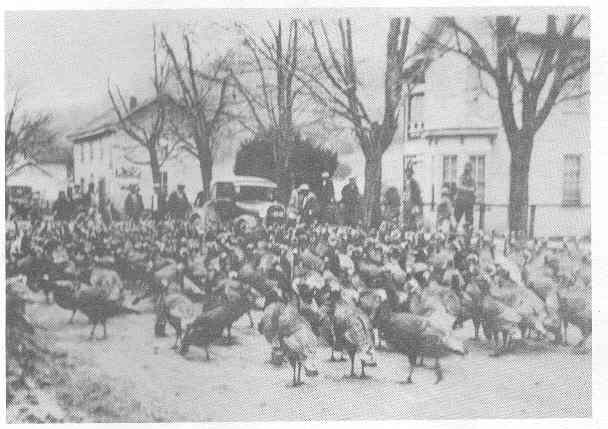

business loans for Citizens Bank of East Tennessee in Sneedville. On his office wall is a

photograph, taken, he thinks, around 1912. It depicts dozens of turkeys on the grounds of the

Hancock County Courthouse, about to be driven in the direction of the Clinch River.

“Hundreds of turkeys would be gathered in the springtime each year, and in late fall,”

according to Scott. “They were first taken down to the Clinch River, south of Sneedville. At that

time there was no bridge, so they had to be moved across the river by ferry.

“The ferry was filled with turkeys, pulled to the other side by a cable, where somebody

would stay with the turkeys, and then they’d pull the ferry back and take a few more over. This

went on until they got all the turkeys to the south side of the river.”

From there, they were herded down a path to Morristown.

“It made no difference where they were, if dark came, the turkeys decided where they

wanted to roost,” Scott tells me. “And of course farmers carried along feed, because the turkeys

would lose weight along the way. What a task that must have been.”

After all the labor and hardship, Scott says the turkey herders were totally at the mercy of

the buyers in Morristown and Rogersville. Sometimes the farmers got the price they expected;

oftentimes they didn’t. But they couldn’t turn back and had to accept the offer. Although the

turkey drives seem humorous from the perspective of the 21st century, Scott says they were typical of the extremes people in the mountains had to go to in order to survive.

“The turkey drive was a way for folks to make some extra money to feed their families,

especially at Christmastime. They were hoping to get enough cash to get them through the

Christmas holidays. And it was a matter of survival. People in this area had it tough, and they

still have it tough.”

Scott tells his turkey story to schoolchildren around Hancock County, graphically

describing how the turkeys must have “moped along,” in no hurry to get anywhere, and how

some of them likely escaped along the way.

Improved transportation, and probably accumulated fatigue, ended the turkey drives.

Scott Collins says people today have a hard time believing the drives ever occurred. But they did,

and that photograph of soon-to-be-herded turkeys searching the ground for food in front of the

Hancock County Courthouse is proof.